|

|

|

|

|

Gulliver's Travels: Voyage To LilliputBy JONATHAN SWIFTADAPTED BY JOHN LANG

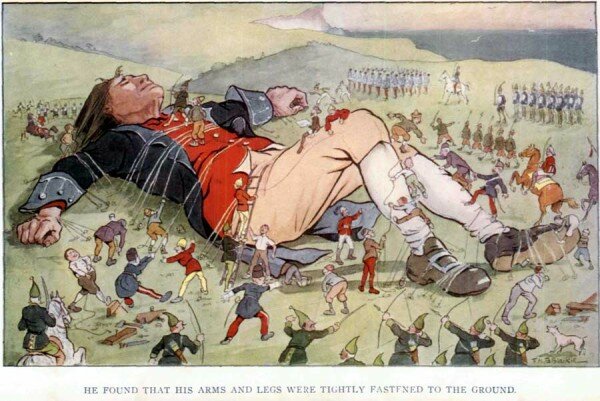

I. GULLIVER'S BIRTH AND EARLY VOYAGESTwo hundred years ago, a great deal of the world as we now know it was still undiscovered; there were yet very many islands, small and great, on which the eyes of white men had never looked, seas in which nothing bigger than an Indian canoe had ever sailed. A voyage in those days was not often a pleasant thing, for ships then were very bluff-bowed and slow-sailing, and, for a long voyage, very ill-provided with food. There were no tinned meats two hundred years ago, no luxuries for use even in the cabin. Sailors lived chiefly on salt junk, as hard as leather, on biscuit that was generally as much weevil as biscuit, and the water that they drank was evil-smelling and bad when it had been long in the ship's casks. So, when a man said good-by to his friends and sailed away into the unknown, generally very many years passed before he came back—if ever he came back at all. For the dangers of the seas were then far greater than they now are, and if a ship was not wrecked some dark night on an unknown island or uncharted reef, there was always the probability of meeting a pirate vessel and of having to fight for life and liberty. Steam has nowadays nearly done away with pirates, except on the China coast and in a few other out-of-the-way places. But things were different long ago, before steamers were invented; and sailors then, when they came home, had many very surprising things to tell their friends, many astonishing adventures to speak of, among the strange peoples that they said they had met in far-off lands. One man, who saw more wonderful things than any one else, was named Lemuel Gulliver, and I will try to tell you a little about one of his voyages. Gulliver was born in Nottinghamshire, and when he was only fourteen years old he was sent to Emanuel College, Cambridge. There he remained till he was seventeen, but his father had not money enough to keep him any longer at the University. So, as was then the custom for those who meant to become doctors, he was bound apprentice to a surgeon in London, under whom he studied for four years. But all the time, as often as his father sent him money, he spent some of it in learning navigation (which means the art of finding your way across the sea, far from land). He had always had a great longing to travel, and he thought that a knowledge of navigation would be of use to him if he should happen to go a voyage. After leaving London, he went to Germany, and there studied medicine for some years, with the view of being appointed surgeon of a ship. And by the help of his late master in London, such a post he did get on board the "Swallow" on which vessel he made several voyages. But tiring of this, he settled in London, and, having married, began practise as a doctor. He did not, however, make much money at that, and so for six years he again went to sea as a surgeon, sailing both to the East and to the West Indies. Again tiring of the sea, he once more settled on shore, this time at Wapping, because in that place there are always many sailors, and he hoped to make money by doctoring them. But this turned out badly, and on May 4, 1699, he sailed from Bristol for the South Seas as surgeon of a ship named the "Antelope." II. GULLIVER IS WRECKED ON THE COAST OF LILLIPUTAt first, everything went well, but after leaving the South Seas, when steering for the East Indies, the ship was driven by a great storm far to the south. The gale lasted so long that twelve of the crew died from the effects of the hard work and the bad food, and all the others were worn out and weak. On a sailing ship, when the weather is very heavy, all hands have to be constantly on deck, and there is little rest for the men. Perhaps a sail, one of the few that can still be carried in such a gale, may be blown to ribbons by the furious wind, and a new one has to be bent on. The night, perhaps, is dark, the tattered canvas is thrashing with a noise like thunder, the ship burying her decks under angry black seas every few minutes. The men's hands are numb with the cold and the wet, and the hard, dangerous work aloft. There is no chance of going below when their job is done, to "turn in" between warm, dry blankets in a snug berth. Possibly even those who belong to the "watch below" may have to remain on deck. Or, if they have the good fortune to be allowed to go below, they may no sooner have dropped off asleep (rolled round in blankets which perhaps have been wet ever since the gale began) than there is a thump, thump overhead, and one of the watch on deck bellows down the forecastle-hatch, "All hands shorten sail." And out they must tumble again, once more to battle with the hungry, roaring seas and the raging wind. So, when there has been a long spell of bad weather, it is no wonder that the men are worn out. And when, as was the case with Gulliver's ship, the food also is bad, it is easy to understand why so many of the crew had died. It was on the 5th of November, the beginning of summer in latitudes south of the equator. The storm had not yet cleared off, and the weather was very thick, the wind coming in furious squalls that drove the ship along at great speed, when suddenly from the lookout man came a wild cry—"Breakers ahead!" But so close had the vessel come to the rocks before they were seen through the thick driving spray, that immediately, with, a heavy plunge, she crashed into the reef, and split her bows.  he found that his arms and legs were tightly fastened to the ground Gulliver and six of the crew lowered a boat and got clear of the wreck and of the breakers. But the men were so weak from overwork that they could not handle the boat in such a sea, and very soon, during a fierce squall, she sank. What became of the men Gulliver never knew, for he saw none of them again. Probably they were drowned at once, for they were too weak to keep long afloat in a sea breaking so heavily. And indeed, Gulliver himself was like to have been lost. He swam till no strength or feeling was left in his arms and legs, swam bravely, his breath coming in great sobs, his eyes blinded with the salt seas that broke over his head. Still he struggled on, utterly spent, until at last, in a part where the wind seemed to have less force, and the seas swept over him less furiously, on letting down his legs he found that he was within his depth. But the shore shelved so gradually that for nearly a mile he had to wade wearily through shallow water, till, fainting almost with fatigue, he reached dry land. By this time darkness was coming on, and there were no signs of houses or of people. He staggered forward but a little distance, and then, on the short, soft turf, sank down exhausted and slept. When he woke, the sun was shining, and he tried to rise; but not by any means could he stir hand or foot. Gulliver had fallen asleep lying on his back, and now he found that his arms and legs were tightly fastened to the ground. Across his body were numbers of thin but strong cords, and even his hair, which was very long, was pegged down so securely that he could not turn his head. All round about him there was a confused sound of voices, but he could see nothing except the sky, and the sun shone so hot and fierce into his eyes that he could scarcely keep them open. Soon he felt something come gently up his left leg, and forward on to his breast almost to his chin. Looking down as much as possible, he saw standing there a very little man, not more than six inches high, armed with a bow and arrows. Then many more small men began to swarm over him. Gulliver let out such a roar of wonder and fright that they all turned and ran, many of them getting bad falls in their hurry to get out of danger. But very quickly the little people came back again. This time, with a great struggle Gulliver managed to break the cords that fastened his left arm, and at the same time, by a violent wrench that hurt him dreadfully, he slightly loosened the strings that fastened his hair, so that he was able to turn his head a little to one side. But the little men were too quick for him, and got out of reach before he could catch any of them. Then he heard a great shouting, followed by a shrill little voice that called sharply, "Tolgo phonac," and immediately, arrows like needles were shot into his hand, and another volley struck him in the face. Poor Gulliver covered his face with his hand, and lay groaning with pain. Again he struggled to get loose. But the harder he fought for freedom, the more the little men shot arrows into him, and some of them even tried to run their spears into his sides. When he found that the more he struggled the more he was hurt, Gulliver lay still, thinking to himself that at night at least, now that his left hand was free, he could easily get rid of the rest of his bonds. As soon as the little people saw that he struggled no more, they ceased shooting at him; but he knew from the increasing sound of voices that more and more of the little soldiers were coming round him. Soon, a few yards from him, on the right, he heard a continued sound of hammering, and on turning his head to that side as far as the strings would let him, he saw that a small wooden stage was being built. On to this, when it was finished, there climbed by ladders four men, and one of them (who seemed to be a very important person, for a little page boy attended to hold up his train) immediately gave an order. At once about fifty of the soldiers ran forward and cut the strings that tied Gulliver's hair on the left side, so that he could turn his head easily to the right. Then the person began to make a long speech, not one word of which could Gulliver understand, but it seemed to him that sometimes the little man threatened, and sometimes made offers of kindness. As well as he could, Gulliver made signs that he submitted. Then, feeling by this time faint with hunger, he pointed with his fingers many times to his mouth, to show that he wanted something to eat. They understood him very well. Several ladders were put against Gulliver's sides, and about a hundred little people climbed up and carried to his mouth all kinds of bread and meat. There were things shaped like legs, and shoulders, and saddles of mutton. Very good they were, Gulliver thought, but very small, no bigger than a lark's wing; and the loaves of bread were about the size of bullets, so that he could take several at a mouthful. The people wondered greatly at the amount that he ate. When he signed that he was thirsty, they slung up on to his body two of their biggest casks of wine, and having rolled them forward to his hand they knocked out the heads of the casks. Gulliver drank them both off at a draught, and asked for more, for they held only about a small tumblerful each. But there was no more to be had. As the small people walked to and fro over his body, Gulliver was sorely tempted to seize forty or fifty of them and dash them on the ground, and then to make a further struggle for liberty. But the pain he had already suffered from their arrows made him think better of it, and he wisely lay quiet. Soon another small man, who from his brilliant uniform seemed to be an officer of very high rank, marched with some others on to Gulliver's chest and held up to his eyes a paper which Gulliver understood to be an order from the King of the country. The officer made a long speech, often pointing towards something a long way off, and (as Gulliver afterwards learned) told him that he was to be taken as a prisoner to the city, the capital of the country. Gulliver asked, by signs, that his bonds might be loosed. The officer shook his head and refused, but he allowed some of his soldiers to slack the cords on one side, whereby Gulliver was able to feel more comfortable. After this, the little people drew out the arrows that still stuck in his hands and face, and rubbed the wounds with some pleasant-smelling ointment, which so soothed his pain that very soon he fell sound asleep. And this was no great wonder, for, as he afterwards understood, the King's physicians had mixed a very strong sleeping draught with the wine that had been given him. Gulliver awoke with a violent fit of sneezing, and with the feeling of small feet running away from off his chest. Where was he? Bound still, without doubt, but no longer did he find himself lying on the ground. It puzzled him greatly that now he lay on a sort of platform. How had he got there? Soon he began to realize what had happened; and later, when he understood the language, he learned all that had been done to him while he slept. Before he dropped asleep, he had heard a rumbling as of wheels, and the shouts of many drivers. This, it seemed, was caused by the arrival of a huge kind of trolley, a few inches high, but nearly seven feet long, drawn by fifteen hundred of the King's largest horses. On this it was meant that he should be taken to the city. By the use of strong poles fixed in the ground, to which were attached many pulleys, and the strongest ropes to be found in the country, nine hundred men managed to hoist him as he slept. They then put him on the trolley, where they again tied him fast. It was when they were far on their way to the city that Gulliver awoke. The trolley had stopped for a little to breathe the horses, and one of the officers of the King's Guard who had not before seen Gulliver, climbed with some friends up his body. While looking at his face, the officer could not resist the temptation of putting the point of his sword up Gulliver's nose, which tickled him so that he woke, sneezing violently. III. GULLIVER IS TAKEN AS A PRISONER TO THE CAPITAL OF LILLIPUTThe city was not reached till the following day, and Gulliver had to spend the night lying where he was, guarded on each side by five hundred men with torches and bows and arrows, ready to shoot him if he should attempt to move. In the morning, the King and all his court, and thousands of the people, came out to gaze on the wonderful sight. The trolley, with Gulliver on it, stopped outside the walls, alongside a very large building which had once been used as a temple, but the use of which had been given up owing to a murder having been committed in it. The door of this temple was quite four feet high and about two feet wide, and on each side, about six inches from the ground, was a small window. Inside the building the King's blacksmiths fastened many chains, which they then brought through one of these little windows and padlocked round Gulliver's left ankle. Then his bonds were cut, and he was allowed to get up. He found that he could easily creep through the door, and that there was room inside to lie down. His chains were nearly six feet long, so that he could get a little exercise by walking backwards and forwards outside. Always when he walked, thousands of people thronged around to look at him; even the King himself used to come and gaze by the hour from a high tower which stood opposite. One day, just as Gulliver had crept out from his house and had got on his feet, it chanced that the King, who was a very fine-looking man, taller than any of his people, came riding along on his great white charger. When the horse saw Gulliver move it was terrified, and plunged and reared so madly that the people feared that a terrible accident was going to happen, and several of the King's guards ran in to seize the horse by the head. But the King was a good horseman, and managed the animal so well that very soon it got over its fright, and he was able to dismount. Then he gave orders that food should be brought for Gulliver, twenty little carts full, and ten of wine; and he and his courtiers, all covered with gold and silver, stood around and watched him eating. After the King had gone away the people of the city crowded round, and some of them began to behave very badly, one man even going so far as to shoot an arrow at Gulliver which was not far from putting out one of his eyes. But the officer in command of the soldiers who were on guard ordered his men to bind and push six of the worst behaved of the crowd within reach of Gulliver, who at once seized five of them and put them in his coat pocket. The sixth he held up to his mouth and made as if he meant to eat him, whereupon the wretched little creature shrieked aloud with terror, and when Gulliver took out his knife, all the people, even the soldiers, were dreadfully alarmed. But Gulliver only cut the man's bonds, and let him run away, which he did in a great hurry. And when he took the others out of his pocket, one by one, and treated them in the same way, the crowd began to laugh. After that the people always behaved very well to Gulliver, and he became a great favorite. From all over the kingdom crowds flocked to see the Great Man Mountain. In the meantime, as Gulliver learned later, there were frequent meetings of the King's council to discuss the question of what was to be done with him. Some of the councilors feared lest he might break loose and cause great damage in the city. Some were of opinion that to keep and feed so huge a creature would cause a famine in the land, or, at the least, that the expense would be greater than the public funds could bear; they advised, therefore, that he should be killed—shot in the hands and face with poisoned arrows. Others, however, argued that if this were done it would be a very difficult thing to get rid of so large a dead body, which might cause a pestilence to break out if it lay long unburied so near the city. Finally, the King and his council gave orders that each morning the surrounding villages should send into the city for Gulliver's daily use six oxen, forty sheep, and a sufficient quantity of bread and wine. It was also commanded that six hundred persons should act as his servants; that three hundred tailors were to make for him a suit of clothes; and that six professors from the University were to teach him the language of the country. When Gulliver could speak the language, he learned a great deal about the land in which he now found himself. It was called Lilliput, and the people, Lilliputians. These Lilliputians believed that their kingdom and the neighboring country of Blefuscu were the whole world. Blefuscu lay far over the sea, to these little people dim and blue on the horizon, though to Gulliver the distance did not seem to be more than a mile. The Lilliputians knew of no land beyond Blefuscu. And as for Gulliver himself, they believed that he had fallen from the moon, or from one of the stars; it was impossible, they said, that so big a race of men could live on the earth. It was quite certain that there could not be food enough for them. They did not believe Gulliver's story. He must have fallen from the moon! Almost the first thing that Gulliver did when he knew the language fairly well, was to send a petition to the King, praying that his chains might be taken off and that he might be free to walk about. But this he was told could not then be granted. He must first, the King's council said, "swear a peace" with the kingdom of Lilliput, and afterwards, if by continued good behavior he gained their confidence, he might be freed. Meantime, by the King's orders, two high officers of state were sent to search him, Gulliver lifted up these officers in his hand and put them into each of his pockets, one after the other, and they made for the King a careful list of everything found there. Gulliver afterward saw this inventory. His snuff-box they had described as a "huge silver chest, full of a sort of dust." Into that dust one of them stepped, and the snuff, flying up in his face, caused him nearly to sneeze his head off. His pistols they called "hollow pillars of iron, fastened to strong pieces of timber," and the use of his bullets, and of his powder (which he had been lucky enough to bring ashore dry, owing to his pouch being water-tight), they could not understand, while of his watch they could make nothing. They called it "a wonderful kind of engine, which makes an incessant noise like a water-wheel." But some fancied that it was perhaps a kind of animal. Certainly it was alive. All these things, together with his sword, which he carried slung to a belt round his waist, Gulliver had to give up, first, as well as he could, explaining the use of them. The Lilliputians could not understand the pistols, and to show his meaning, Gulliver was obliged to fire one of them. At once hundreds of little people fell down as if they had been struck dead by the noise. Even the King, though he stood his ground, was sorely frightened. Most of Gulliver's property was returned to him; but the pistols and powder and bullets, and his sword, were taken away and put, for safety, under strict guard. As the King and his courtiers gained more faith in Gulliver, and became less afraid of his breaking loose and doing some mischief, they began to treat him in a more friendly way than they had hitherto done, and showed him more of the manners and customs of the country. Some of these were very curious. One of the sports of which they were most fond was rope-dancing, and there was no more certain means of being promoted to high office and power in the state than to possess great cleverness in that art. Indeed, it was said that the Lord High Treasurer had gained and kept his post chiefly through his great skill in turning somersaults on the tight rope. The Chief Secretary for private affairs ran him very close, and there was hardly a Minister of State who did not owe his position to such successes. Few of them, indeed, had escaped without severe accidents at one time or another, while trying some specially difficult feat, and many had been lamed for life. But however many and bad the falls, there were always plenty of other persons to attempt the same or some more difficult jump. Taught by his narrow escape from a serious accident when his horse first saw Gulliver, the King now gave orders that the horses of his army, as well as those from the Royal stables, should be exercised daily close to the Man Mountain. Soon they became so used to the sight of him that they would come right up to his foot without starting or shying. Often the riders would jump their chargers over Gulliver's hand as he held it on the ground; and once the King's huntsman, better mounted than most of the others, actually jumped over his foot, shoe and all—a wonderful leap. Gulliver saw that it was wise to amuse the King in this and other ways, because the more his Majesty was pleased with him the sooner was it likely that his liberty would be granted. So he asked one day that some strong sticks, about two feet in height, should be brought to him. Several of these he fixed firmly in the ground, and across them, near the top, he lashed four other sticks, enclosing a square space of about two and a half feet. Then to the uprights, about five inches lower than the crossed sticks, he tied his pocket-handkerchief, and stretched it tight as a drum. When the work was finished, he asked the King to let a troop exercise on this stage. His Majesty was delighted with the idea, and for several days nothing pleased him more than to see Gulliver lift up the men and horses, and to watch them go through their drill on this platform. Sometimes he would even be lifted up himself and give the words of command; and once he persuaded the Queen, who was rather timid, to let herself be held up in her chair within full view of the scene. But a fiery horse one day, pawing with his hoof, wore a hole in the handkerchief, and came down heavily on its side, and after this Gulliver could no longer trust the strength of his stage. IV. GULLIVER IS FREED, AND CAPTURES THE BLEFUSCAN FLEETBy this time Gulliver's clothes were almost in rags. The three hundred tailors had not yet been able to finish his new suit, and he had no hat at all, for that had been lost as he came ashore from the wreck. So he was greatly pleased one day when an express message came to the King from the coast, saying that some men had found on the shore a great, black, strangely-shaped mass, as high as a man; it was not alive, they were certain. It had never moved, though for a time they had watched, before going closer. After making certain that it was not likely to injure them, by mounting on each other's shoulders they had got on the top, which they found was flat and smooth, and, by the sound when stamped upon, they judged that it was hollow. It was thought that the object might possibly be something belonging to the Man Mountain, and they proposed by the help of five horses to bring it to the city. Gulliver was sure that it must be his hat, and so it turned out. Nor was it very greatly damaged, either by the sea or by being drawn by the horses over the ground all the way from the coast, except that two holes had been bored in the brim, to which a long cord had been fixed by hooks. Gulliver was much pleased to have it once more. Two days after this the King took into his head a curious fancy. He ordered a review of troops to be held, and he directed that Gulliver should stand with his legs very wide apart, while under him both horse and foot were commanded to march. Over three thousand infantry and one thousand cavalry passed through the great arch made by his legs, colors flying and bands playing. The King and Queen themselves sat in their State Coach at the saluting point, near to his left leg, and all the while Gulliver dared not move a hair's-breadth, lest he should injure some of the soldiers.  gulliver in lilliput Shortly after this, Gulliver was set free. There had been a meeting of the King's Council on the subject, and the Lord High Admiral was the only member in favor of still keeping him chained. This great officer to the end was Gulliver's bitter enemy, and though on this occasion he was out-voted, yet he was allowed to draw up the conditions which Gulliver was to sign before his chains were struck off. The conditions were: First, that he was not to quit the country without leave granted under the King's Great Seal. Second, that he was not to come into the city without orders; at which times the people were to have two hours' notice to keep indoors. Third, that he should keep to the high roads, and not walk or lie down in a meadow. Fourth, that he was to take the utmost care not to trample on anybody, or on any horses or carriages, and that he was not to lift any persons in his hand against their will. Fifth, that if at any time an express had to be sent in great haste, he was to carry the messenger and his horse in his pocket a six-days' journey, and to bring them safely back. Sixth, that he should be the King's ally against the Blefuscans, and that he should try to destroy their fleet, which was said to be preparing to invade Lilliput. Seventh, that he should help the workmen to move certain great stones which were needed to repair some of the public buildings. Eighth, that he should in "two moons' time" make an exact survey of the kingdom, by counting how many of his own paces it took him to go all round the coast. Lastly, on his swearing to the above conditions, it was promised that he should have a daily allowance of meat and drink equal to the amount consumed by seventeen hundred and twenty-four of the Lilliputians, for they estimated that Gulliver's size was about equal to that number of their own people. Though one or two of the conditions did not please him, especially that about helping the workmen (which he thought was making him too much a servant), yet Gulliver signed the document at once, and swore to observe its conditions. After having done so, and having had his chains removed, the first thing he asked was to be allowed to see the city (which was called Mildendo). He found that it was surrounded by a great wall about two and a half feet high, broad enough for one of their coaches and four to be driven along, and at every ten feet there were strong flanking towers. Gulliver took off his coat, lest the tails might do damage to the roofs or chimneys of the houses, and he then stepped over the wall and very carefully walked down the finest of the streets, one quite five feet wide. Wherever he went, the tops of the houses and the attic windows were packed with wondering spectators, and he reckoned that the town must hold quite half a million of people. In the center of the city, where the two chief streets met, stood the King's Palace, a very fine building surrounded by a wall. But he was not able to see the whole palace that day, because the part in which were the royal apartments was shut off by another wall nearly five feet in height, which he could not get over without a risk of doing damage. Some days later he climbed over by the help of two stools which he made from some of the largest trees in the Royal Park, trees nearly seven feet high, which he was allowed to cut down for the purpose. By putting one of the stools at each side of the wall Gulliver was able to step across. Then, lying down on his side, and putting his face close to the open windows, he looked in and saw the Queen and all the young Princes. The Queen smiled, and held her hand out of one of the windows, that he might kiss it. She was very pleasant and friendly. One day, about a fortnight after this, there came to call on him, Reldresal, the King's Chief Secretary, a very great man, one who had always been Gulliver's very good friend. This person had a long and serious talk with Gulliver about the state of the country. He said that though to the outward eye things in Lilliput seemed very settled and prosperous, yet in reality there were troubles, both internal and external, that threatened the safety of the kingdom. There had been in Lilliput for a very long time two parties at bitter enmity with each other, so bitter that they would neither eat, drink, nor talk together, and what one party did, the other would always try to undo. Each professed to believe that nothing good could come from the other. Any measure proposed by the party in power was by the other always looked upon as foolish or evil. And any new law passed by the Government party was said by the Opposition to be either a wicked attack on the liberties of the people, or something undertaken solely for the purpose of keeping that party in, and the Opposition out, of power. To such a pitch had things now come, said the Chief Secretary, entirely owing to the folly of the Opposition, that the business of the kingdom was almost at a standstill. Meantime the country was in danger of an invasion by the Blefuscans, who were now fitting out a great fleet, which was almost ready to sail to attack Lilliput. The war with Blefuscu had been raging for some years, and the losses by both nations of ships and of men had been very heavy. This war had broken out in the following way. It had always been the custom in Lilliput, as far back as history went, for people when breaking an egg at breakfast to do so at the big end. But it had happened, said the Chief Secretary, that the present King's grandfather, when a boy, had once when breaking his egg in the usual way, severely cut his finger. Whereupon his father at once gave strict commands that in future all his subjects should break their eggs at the small end. This greatly angered the people, who thought that the King had no right to give such an order, and they refused to obey. As a consequence no less than six rebellions had taken place: thousands of the Lilliputians had had their heads cut off, or had been cast into prison, and thousands had fled for refuge to Blefuscu, rather than obey the hated order. These "Big endians," as they were called, had been very well received at the Court of Blefuscu, and finally the Emperor of that country had taken upon himself to interfere in the affairs of Lilliput, thus bringing on war. The Chief Secretary ended the talk by saying that the King, having great faith in Gulliver's strength, and depending on the oath which he had sworn before being released, expected him now to help in defeating the Blefuscan fleet. Gulliver was very ready to do what he could, and he at once thought of a plan whereby he might destroy the whole fleet at one blow. He told all his ideas on the subject to the King, who gave orders that everything he might need should be supplied without delay. Then Gulliver went to the oldest seamen in the navy, and learned from them the depth of water between Lilliput and Blefuscu. It was, they said, nowhere deeper than seventy glumgluffs (which is equal to about six feet) at high water, and there was no great extent so deep. After this he walked to the coast opposite Blefuscu, and lying down there behind a hillock, so that he might not be seen should any of the enemy's ships happen to be cruising near, he looked long through a small pocket-telescope across the channel. With the naked eye he could easily see the cliffs of Blefuscu, and soon with his telescope he made out where the fleet lay—fifty great men-of-war, and many transports, waiting for a fair wind. Coming back to the city, he gave orders for a great length of the strongest cable, and a quantity of bars of iron. The cable was little thicker than ordinary pack-thread, and the bars of iron much about the length and size of knitting-needles. Gulliver twisted three of the iron bars together and bent them to a hook at one end. He trebled the cable for greater strength, and thus made fifty shorter cables, to which he fastened the hooks. Then, carrying these in his hand, he walked back to the coast and waded into the sea, a little before high water. When he came to mid-channel, he had to swim, but for no great distance. As soon as they noticed Gulliver coming wading through the water towards their ships, the Blefuscan sailors all jumped overboard and swam ashore in a terrible fright. Never before had any of them seen or dreamt of so monstrous a giant, nor had they heard of his being in Lilliput. Gulliver then quietly took his cables and fixed one securely in the bows of each of the ships of war, and finally he tied the cables together at his end. But while he was doing this the Blefuscan soldiers on the shore plucked up courage and began to shoot arrows at him, many of which stuck in his hands and face. He was very much afraid lest some of these might put out his eyes; but he remembered, luckily, that in his inner pocket were his spectacles, which he put on, and then finished his work without risk to his eyes. On pulling at the cables, however, not a ship could he move. He had forgotten that their anchors were all down. So he was forced to go in closer and with his knife to cut the vessels free. While doing this he was of course exposed to a furious fire from the enemy, and hundreds of arrows struck him, some almost knocking off his spectacles. But again he hauled, and this time drew the whole fifty vessels after him. The Blefuscans had thought that it was his intention merely to cast the vessels adrift, so that they might run aground, but when they saw their great fleet being steadily drawn out to sea, their grief was terrible. For a great distance Gulliver could hear their cries of despair. When he had got well away from the land, he stopped in order to pick the arrows from his face and hands, and to put on some of the ointment that had been rubbed on his wounds when first the Lilliputians fired into him. By this time the tide had fallen a little, and he was able to wade all the way across the channel. The King and his courtiers stood waiting on the shore. They could see the vessels steadily drawing nearer, but they could not for some time see Gulliver, because only his head was above water. At first some imagined that he had been drowned, and that the fleet was now on its way to attack Lilliput. There was great joy when Gulliver was seen hauling the vessels; and when he landed, the King was so pleased that on the spot he created him a Nardac, the highest honor that it was in his power to bestow. His great success over the Blefuscans, however, turned out to be but the beginning of trouble for Gulliver. The King was so puffed up by the victory that he formed plans for capturing in the same way the whole of the enemy's ships of every kind. And it was now his wish to crush Blefuscu utterly, and to make it nothing but a province depending on Lilliput. Thus, he thought, he himself would then be monarch of the whole world. In this scheme Gulliver refused to take any part, and he very plainly said that he would give no help in making slaves of the Blefuscans. This refusal angered the King very much, and more than once he artfully brought the matter up at a State Council. Now, several of the councilors, though they pretended to be Gulliver's friends so long as he was in favor with the King, were really his secret enemies, and nothing pleased these persons better than to see that the King was no longer pleased with him. So they did all in their power to nurse and increase the King's anger, and to make him believe that Gulliver was a traitor. About this time there came to Lilliput ambassadors from Blefuscu, suing for peace. When a treaty had been made and signed (very greatly to the advantage of Lilliput), the Blefuscan ambassadors asked to see the Great Man Mountain, of whom they had heard so much, and they paid Gulliver a formal call. After asking him to give them some proofs of his strength, they invited him to visit their Emperor, which Gulliver promised to do. Accordingly, the next time that he met the King, he asked, as he was bound to do by the paper he had signed, for permission to leave the country for a time, in order to visit Blefuscu. The King did not refuse, but his manner was so cold that Gulliver could not help noticing it. Afterwards he learned from a friend that his enemies in the council had told the King lying tales of his meetings with the Blefuscan ambassadors, which had had the effect of still further rousing his anger. It happened too, most unfortunately, at this time, that Gulliver had offended the Queen by a well-meant, but badly-managed, effort to do her a service, and thus he lost also her friendship. But though he was now out of favor at court, he was still an object of great interest to every one.  on this occasion, gulliver ate more than usual V. GULLIVER'S ESCAPE FROM LILLIPUT AND RETURN TO ENGLANDGulliver had three hundred cooks to dress his food and these men, with their families, lived in small huts which had been built for them near his house. He had made for himself a chair and a table. On to this table it was his custom to lift twenty waiters, and these men then drew up by ropes and pulleys all his food, and his wine in casks, which one hundred other servants had in readiness on the ground. Gulliver would often eat his meal with many hundreds of people looking on. One day the King, who had not seen him eat since this table had been built, sent a message that he and the Queen desired to be present that day while Gulliver dined. They arrived just before his dinner hour, and he at once lifted the King and Queen and the Princes, with their attendants and guards, on to the table. Their Majesties sat in their chairs of state all the time, watching with deep interest the roasts of beef and mutton, and whole flocks of geese and turkeys and fowls disappear into Gulliver's mouth. A roast of beef of which he had to make more than two mouthfuls was seldom seen, and he ate them bones and all. A goose or a turkey was but one bite. Certainly, on this occasion, Gulliver ate more than usual, thinking by so doing to amuse and please the court. But in this he erred, for it was turned against him. Flimnap, the Lord High Treasurer, who had always been one of his enemies, pointed out to the King the great daily expense of such meals, and told how this huge man had already cost the country over a million and a half of sprugs (the largest Lilliputian gold coin). Things, indeed, were beginning to go very ill with Gulliver. Now it happened about this time that one of the King's courtiers, to whom Gulliver had been very kind, came to him by night very privately in a closed chair, and asked to have a talk, without any one else being present. Gulliver gave to a servant whom he could trust orders that no one else was to be admitted, and having put the courtier and his chair upon the table, so that he might better hear all that was said, he sat down to listen. Gulliver was told that there had lately been several secret meetings of the King's Privy Council, on his account. The Lord High Admiral (who now hated him because of his success against the Blefuscan fleet), Flimnap, the High Treasurer, and others of his enemies, had drawn up against him charges of treason and other crimes. The courtier had brought with him a copy of these charges, and Gulliver now read them. It was made a point against him that, when ordered to do so by the King, he had refused to seize all the other Blefuscan ships. It was also said that he would not join in utterly crushing the empire of Blefuscu, nor give aid when it was proposed to put to death not only all the Big endians who had fled for refuge to that country, but all the Blefuscans themselves who were friends of the Big-endians. For this he was said to be a traitor. He was also accused of being over-friendly with the Blefuscan ambassadors; and it was made a grave charge against him that though his Majesty had not given him written leave to visit Blefuscu, he yet was getting ready to go to that country, in order to give help to the Emperor against Lilliput. There had been many debates on these charges, said the courtier, and the Lord High Admiral had made violent speeches, strongly advising that the Great Man Mountain should be put to death. In this he was joined by Flimnap, and by others, so that actually the greater part of the council was in favor of instant death by the most painful means that could be used. The less unfriendly members of the council, however, while saying that they had no doubt of Gulliver's guilt, were yet of the opinion that, as his services to the kingdom of Lilliput had been great, the punishment of death was too severe. They thought it would be enough if his eyes were put out. This, they said, would not prevent him from being still made useful. Then began a most excited argument, the Admiral and those who sided with him insisting that Gulliver should be killed at once. At last the Secretary rose and said that he had a middle course to suggest. This was, that Gulliver's eyes should be put out, and that thereafter his food should be gradually so reduced in quantity that in the course of two or three months he would die of starvation. By which time, said the Secretary, his body would be wasted to an extent that would make it easy for five or six hundred men, in a few days, to cut off the flesh and take it away in cart-loads to be buried at a distance. Thus there would be no danger of a pestilence breaking out from the dead body lying near the city. The skeleton, he said, could then be put in the National Museum. It was finally decided that this sentence should be carried out, and twenty of the King's surgeons were ordered to be present in three days' time to see the operation of putting out Gulliver's eyes properly done. Sharp-pointed arrows were to be shot into the balls of his eyes. The courtier now left the house, as privately as he had come, and Gulliver was left to decide what he should do. At first he thought of attacking the city, and destroying it. But by doing this he must have destroyed, with the city, a great many thousands of innocent people, which he could not make up his mind to do. At last he wrote a letter to the Chief Secretary, saying that as the King had himself told him that he might visit Blefuscu, he had decided to do so that morning. Without waiting for an answer, he set out for the coast, where he seized a large man-of-war which was at anchor there, tied a cable to her bow, and then putting his clothes and his blanket on board, he drew the ship after him to Blefuscu. There he was well received by the Emperor. But as there happened to be no house big enough for him, he was forced, during his stay, to sleep each night on the ground, wrapped in his blanket. Three days after his arrival, when walking along the seashore, he noticed something in the water which looked not unlike a boat floating bottom up. Gulliver waded and swam out, and found that he was right. It was a boat. By the help of some of the Blefsucan ships, with much difficulty he got it ashore. When the tide had fallen, two thousand of the Emperor's dockyard men helped him to turn it over, and Gulliver found that but little damage had been done. He now set to work to make oars and mast and sail for the boat, and to fit it out and provision it for a voyage. While this work was going on, there came from Lilliput a message demanding that Gulliver should be bound hand and foot and returned to that country as a prisoner, there to be punished as a traitor. To this message the Emperor replied that it was not possible to bind him; that moreover the Great Man Mountain had found a vessel of size great enough to carry him over the sea, and that it was his purpose to leave the Empire of Blefuscu in the course of a few weeks. Gulliver did not delay his work, and in less than a month he was ready to sail. He put on board the boat the carcasses of one hundred oxen and three hundred sheep, with a quantity of bread and wine, and as much meat ready cooked as four hundred cooks could prepare. He also took with him a herd of six live black cows and two bulls, and a flock of sheep, meaning to take them with him to England, if ever he should get there. As food for these animals he took a quantity of hay and corn. Gulliver would have liked to take with him some of the people, but this the Emperor would not permit. Everything being ready, he sailed from Blefuscu on 24th September 1701, and the same night anchored on the lee side of an island which seemed to be uninhabited. Leaving this island on the following morning, he sailed to the eastward for two days. On the evening of the second day he sighted a ship, on reaching which, to his great joy, he found that she was an English vessel on her way home from Japan. Putting his cattle and sheep in his coat-pockets, he went on board with all his cargo of provisions. The captain received him very kindly, and asked him from whence he had come, and how he happened to be at sea in an open boat. Gulliver told his tale in as few words as possible. The captain stared with wonder, and would not believe his story. But Gulliver then took from his pockets the black cattle and the sheep, which of course clearly showed that he had been speaking truth. He also showed gold coins which the Emperor of Blefuscu had given him, some of which he presented to the captain. The vessel did not arrive at the port of London till April, 1702, but there was no loss of the live stock, excepting that the rats on board carried off and ate one of the sheep. All the others were got safely ashore, and were put to graze on a bowling-green at Greenwich, where they throve very well.

|